It is better to leave Tehran for the old road leading to Khorasan province at 5 a.m. because later cars will clog the arteries of the streets of Iran. The central and northern districts of the Iranian capital will remain behind, where irrigation ditches run along the main streets with a cool ringing, and luxury shops sparkle with glass and nickel, reminding us of the oil boom and oil money.

Khorasan province, Iran

The city wakes up with the first rays of the sun. On the sidewalk, at the ministries, modern scribes are already knocking on typewriters, putting simple complaints or requests of illiterate or inexperienced petitioners in clerical flowery. Tea peddlers maneuver in the crowd, like clever football players bypassing the opponent’s defense. Working people storm double-decker buses. Young scions of aristocratic families, having spent the night, cheer themselves up with hot hash from lamb legs and ears.

In the southern districts of Tehran, shabby houses studded with television antennas, adobe fences, and narrow dusty streets will sweep by. You will break out of the city, and if you are lucky with the weather, then in the northeast you will see the shining snow peak of Demavenda-the highest peak of Elbursa and Western Asia.

Urbanization

Despite rapid urbanization, most of Iran’s population cultivates the land, grazes cattle, and grows vegetables and fruits. Agriculture has always been the foundation of Iranian civilization. In one of the ancient Iranian hymns dating back to the first millennium BC, the preacher Zoroaster asks: “Who brings the highest joy to the country?” Ahuramazda, “the embodiment of virtue,” answers: “He who irrigates the desert and drains the swamps to cultivate the fields.”

Today Iran is a big country. It stretches for 3,200 km from northwest to southeast and 1,400 km from north to south. But only a small part of its territory is suitable for agriculture. The rest is a barren, rocky, sometimes saline desert. However, despite droughts and storms, frequent earthquakes, and nomadic raids, oases have always bloomed in the desert. They died and re-emerged from the sand and ashes thanks to the labor of the peasants.

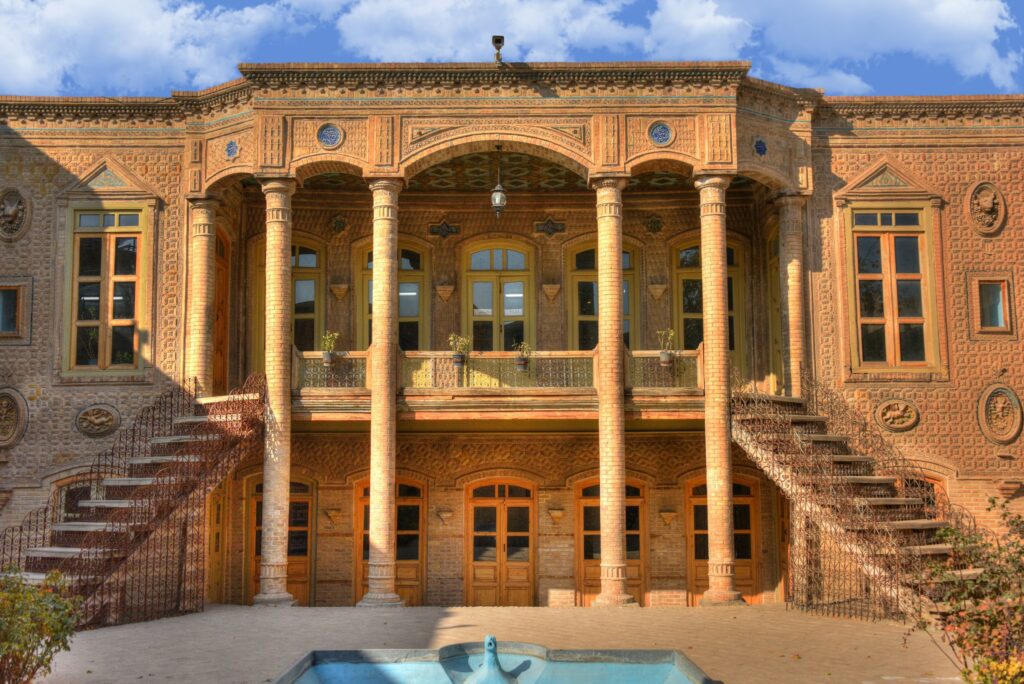

Architecuture, Iran

About 10 years ago, Iran was distinguished by very large land ownership and small-scale land use. There were feudal clans that owned dozens of villages, and there was not even the concept of a “middle peasant”. The harvest of the Persian field was divided into five parts based on five elements: land, seeds, water, working cattle, and labor. The peasant, offering in most cases only labor, received Vs part of the harvest – and then not always. The backwardness of the main sector of the Iranian economy hindered the development of the entire economy. Currently, agrarian reform has been carried out in Iran, and a part of the landlords’ lands has been distributed for ransom.

One of the forms of modern large-scale economy in Iran is considered to be “corporations”. The old Khorasan road led us to the Gyarmsar agricultural Association. It was based on several hundred families from

eight villages that have united their 4 thousand hectares of land in exchange for about 18 thousand shares of shares. The “corporation” constantly employs a large part of the owners of shares and from time to time – half.

In addition to a share of the profits, they receive a salary. The farm employs several hundred seasonal farmhands – after all, 40% of the families of Gyarmsar have never had the land. Shares are freely sold and bought within the “corporation”, so rural businessmen can concentrate more and more shares in their hands. A “corporation” is essentially a joint-stock capitalist company. The state has exempted her from taxes and provides loans. About fifty similar “corporations” have already been created in Iran. So far, they are a drop in the ocean of the Iranian village, and the question is whether they will be viable if they are created on a massive scale.

Tehran, Iran

We turn off the old Khorasan road and enter the new highway through dusty villages. It is part of the great trans-Asian road that runs from Istanbul to Singapore. The highway crosses the spurs of the Elbursa ridge, and we find ourselves as if in another country. Wet winds from the northwest, stopped by the wall of mountains, are resolved here by warm, fertile rains, and the northern provinces adjacent to the Caspian resemble the Kuban or Colchis.

When you immerse yourself in the bustle of the district cities of Khorasan, you are overcome by the tantalizing smell of pita cakes, which are hung like towels on hooks and ropes, the breath of the crowd, the cries of donkeys, the crackle of motorcycles and cars. Ads glorifying the heroes of the American prairies or Japanese karate, Smirnov vodka, or Coca-Cola are striking. You admire the tight bags of beans and rice, the heads of sugar, which the Iranians still prefer to sawn to drink their tea in a bowl, pans with famous Persian sweets, and cages with clucking or quacking animals. Iranians know how to eat and when they set the table, they create a whole work of art from juicy kebabs, fragrant and spicy herbs, pickled garlic, olives, vegetables, and smoked meats. But to find out who is available to this abundance, let’s turn to the Iranian yearbook. If in developed countries the daily diet consists of 3,200 calories, then in Iran there are 2,100 per capita. For many people, lunch is sour milk with flatbread and onions crumbled into it.

Iranian sweets and food

Once upon a time, caravans of merchants walked along the road to Khorasan. Their daily marches were 25-30 kilometers, and at approximately equal intervals there are still ruins of caravanserais. Their courtyards provided shelter, and the outer fortress walls protected them from robbers. Now you can spend the night in one of the larger market towns. It almost certainly has a motel, arranged according to American models, with hot and cold water and glasses in the toilet, sealed in the sanitary paper. But you will not always find traditional Iranian attention here, as the influx of tourists and business people, increased mobility of Iranian society, an increase in the number of cars filled hotels and worsened their service.

The road runs again like a black asphalt ribbon through the dry steppes of the northeast, approaching Khorasan. Both in provincial towns and small villages, schoolchildren meet, and schools are being built – large, stylized medieval madrasas and two- or three-room rooms. Iran is aware that rapid progress is impossible without expanding education. Until now, more than half of the population cannot read and write, in the village up to 75% are illiterate. Iran has recently introduced eight years of free education. But there are not enough schools and teachers. Every Iranian is a poet at heart, but few of them open the book, which is surprising for

a country that is proud of the names of its medieval thinkers. Some explain this by the rapid development of television.

Neyshabur, Razavi Khorasan Province, Iran

Khorasan, which was the center of the Iranian Renaissance 10 centuries ago, has graves that are dear to every Iranian. Of all the great ones, we will name only the name of Omar Khayyam. It was he who won the greatest popularity in Russia and Europe. In Nishapur, the dome of the mausoleum of unusual shape rose above the grave of the sonorous poet and deep sage. People bend over the marble tombstone and whisper poetic lines.

Hundreds of thousands of pilgrims flock to the capital of Khorasan, Mashhad, every year. It houses Astana, the tomb of the eighth Shiite imam, revered by the followers of this branch of Islam. A mausoleum with a gilded dome has been erected over it, its minarets are also lined with gold, and inside there is multi—pood jewelry made of precious metals and stones, a fantastic luxury of decoration. The walls are covered with shards of mirrors and give the impression of a crystal palace. From the outside, the mausoleum itself and the turquoise mosques built around it seem like a decorated caskets, especially when they are illuminated by bright spotlights in the evening.

The museum at the sanctuary is full of rare works of bronze coinage, carpets, weapons, utensils, and priceless manuscripts. By special permission, an attendant armed with a heavy stick with a silver knob can lead a guest through the courtyard of turquoise mosques. Astana, the stronghold of the Muslim clergy, is one of the richest institutions in Iran. Now its funds under the control of the state are invested in factories and hotels, cinemas, and residential buildings, and are directed to the maintenance of hospitals and schools.

Mashhad, Iran

The ensemble of mosques is surrounded by shopping malls. Iran disappoints the traveler with the lack of “oriental exoticism”, and the uniformity of cities. Maybe the last raid of the “exotic” can still be found near Astana, where picturesquely dressed Afghans, proud Baluchi nomads, and their wives with open faces, and rosary merchants wander in the smoke of hookahs.

“Exotica” has been living out its last years in Mashhad. Now in the city, next to women wrapped in shapeless black veils, you see appropriately dressed female students, and next to young theologians in long robes—students in blue jeans and colorful shirts. There are about 4 thousand students at the local university. The Faculty of Theology was joined by the Faculty of Medicine, Engineering, and the Faculty of Exact Sciences. Modernity is being introduced into Mashhad in different ways. Blocks of multi-story and—alas-faceless houses rise on its outskirts. The airport accepts large aircraft.

Using a semi-automatic phone from Mashhad, you can contact Tehran and other major cities.